By Michael Simkin.

2009.

The Israeli art market might be compared to a kosher stew, whose multitude of ingredients result in pieces of genius being esteemed little more than chunks of potato. Emphasis on saleability, in this fiercely competitive arena, means that art, which expresses life honestly without affectation, is often sacrificed to the perpetual search for what is, at least superficially, new.

Of course, the world over, beyond the clinking of champagne glasses and polite conversation, the interface where art and money meet, is bound to get grubby. But in Israel, where life is experienced as through a magnifying glass, it tends to be more so. Clearly though, galleries are not charities, and have to exhibit work which they perceive will be profitable.

Miriam Gamburd

Miriam Gamburd was born in Moldova, graduated the Muchina Art Academy in Leningrad, now St. Petersburg, and moved to Israel in 1977. Both her parents Eugenia and Moisey Gamburd were also well known artists. Miriam herself is a sculptor, painter and drawer, a lecturer in drawing at Bezalel Art Academy in Jerusalem and senior lecturer at Beit Berl College near Kfar Saba. She has exhibited in both private and group exhibitions in Israel, but mostly in Europe. She is also a permanent member of the Parisian Salon d’Automne.

Her studio in the heart of Tel Aviv, is a work of art itself, filled with an eclectic variety of treasures. She is currently putting the finishing touches to a book, a very edgy, artistic and philosophic work, and the culmination of ten years labour. It is called “The Pulse of the Evil Impulse – Love and Abomination in the Talmud and the Midrash.” It is a visual research into the erotic texts of Jewish scripture. Miriam explained to me that when she became interested in the Talmud and Midrash, she was amazed by the erotic stories and anecdotes, which are so often glossed over. Her book contains 80 drawings, in a variety of styles, as well as 70 corresponding quotes from these Jewish religious texts, and five essays she has written in Hebrew, which have been translated into English.

MS: Miriam, whilst you are well known among other artists in Israel, you are not well known by the general public, why do you think this is?

MG: Israeli galleries aren’t very interested in professional artists like me. They don’t want to see technique…that’s not to say that technique is everything… of course technique without feeling is nothing.

MS: And what about museums?

MG: They’re not interested either – I’m not part of the branja” [‘Branja’ is colloquial Hebrew for ‘the popular set’.]

Miriam’s tone is not bitter though. She accepts her situation, and says with a smile: I am free within the walls of the prison that Israeli art is.

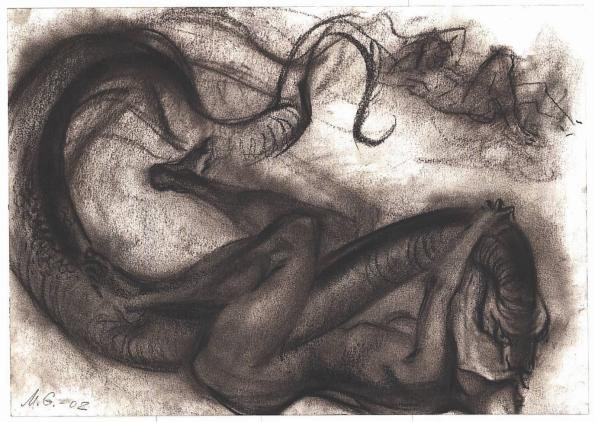

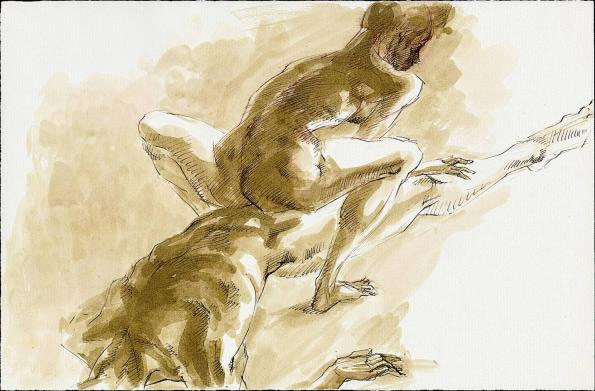

Presented here are two pictures from her new book, followed by two of her sculptures.

This charcoal drawing inspired by chapter 22b of Avoda Zarah, which quotes Rabbi Yochanan, who said: “When the serpent came unto Eve he infused filth into her. If that be so [the same should apply] also to Israel. ” The drawing takes us directly into the eternally consuming power of sexual energy, and with it, its ability to overwhelm us to the point of destruction. This is a picture of violence, but also of acceptance – for nature is violent, and we are bound to it.

This drawing, is inspired by verse 151b of the book Shabbat, which states: “And all who sleep alone in a house are caught by Lilith.” Here Miriam depicts the act of fantasy in a classical style, which manages at the same time to create a sense of freedom and timelessness. It is both erotic and sarcastic, for what choice does man have, but to submit to Lilith?

This sculpture of four heads, in wax, resting together on a single plinth is a representation of passage 54, of Tosafot Yoma, which reads: “The throne of Divine Glory: man, lion, ox and eagle.” It is a secular investigation, which uses the Talmudic tradition, to delve into the various aspects of the singular force of life.

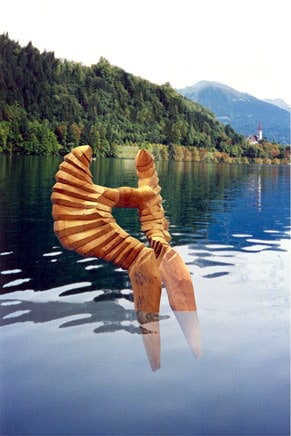

These angelic wings, rising from a Slovakian lake, are made from wood, carved from an old railway sleeper. The sculpture won first place in the Slovakian International Sculpture Prize 2005, and are now exhibited at the Miro Gallery in Bratislava. The wings are an axis mundi, a link between earth and heaven, reminiscent of Excalibur rising from the lake. The angel, whose wings these belong to, is invisible beneath the surface of the water. This mystery seems to point towards the greater mystery of life itself.